Our Classics group is currently reading Euripides' Medea, and of course it brought to mind Ovid's fascination with the enchantress.

|

| Medea rejuvenating Jason's father Aeson |

Ovid was drawn to the daughter of Aeetes. His only tragic drama was his lost Medea. A surviving fragment appears to be an ominous warning from Medea to Jason - and it's pure Ovid:

'servare potui; perderean possim rogas?’

‘I was able to save you; do you think I cannot destroy you?’

Medea dominates half of book 7 of the Metamorphoses. The character and her story develop into something of a travelogue featuring detailed descriptions of her search for the highly rarefied materials of her sorcery. That book can be found here in Tony Kline's translation.

|

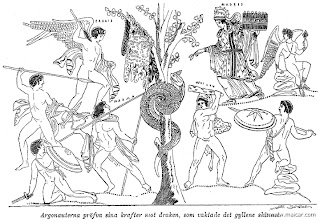

| While Medea puts the Dragon to sleep, Jason, followed by Orpheus, takes the Golden Fleece |

The images of Medea are from Greek Mythology Link, which has a rich "bio" of Medea. The top figure is from a 17th century French translation of the Metamorphoses. The lower one is by William Russell Flint.

This post reproduces what was posted to the Classics in Sarasota blog.

.jpg)