After reading that tale, we might be in a better position to say whether Ovid has dropped his exploration of art and wisdom, or has in fact broadened it. The vast system of Greek myth gave Ovid great latitude -- by moving from the poor country girl (who could equal Athena in spinning) to the daughter of Tantalos, the most powerful queen of her day and sister of Pelops, Ovid seems to be asking us to expand our sense of what the theme, the substance of Book 6, really is.

We move, on one level, from a humble artificer to a noblewoman at the peak of her fortune, from the girl who, like a human parody of Clotho, spun her own fate, to the queen who, presuming to be absolutely in possession of her great good fortune, lived to watch the sudden severance of those lives she thought she had the measure of -- clipped by the shears of Atropos.

Tantalos, Niobe's progenitor, foreshadows her tragic end: As his daughter, she's heir to the strange fortune of her father, who was the most favored of mortals before becoming the most accursed of them.

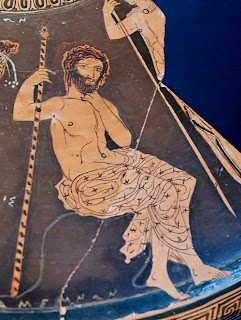

Tantalos, Niobe's progenitor, foreshadows her tragic end: As his daughter, she's heir to the strange fortune of her father, who was the most favored of mortals before becoming the most accursed of them. It would take us farther afield than is reasonable, but the grouping of Tantalos, Sisyphus, Ixion and Tityos is worth exploring when we can, and not only because of their egregious eternal punishments. Tantalos, Sisyphus and Ixion were all unusually favored and gifted. They just went too far (not unlike Prometheus) -- Sisyphus got the better of Hades, Ixion tried to outwit Zeus, and Tantalos has a most peculiar story vis a vis the entire dynasty of the Olympians.

As Pindar says:

that man was Tantalus.

I hope to explore some of the features of the Tantalos figure in another post (I'll link to it here when it's up). It's enough now to note that Ovid, in moving from Arachne to Niobe to Marsyas, is touching on the making of images, of self image, and of voiced music -- before he turns to the tale of Procne and Philomela. The first three tales concern mortals vying with immortals -- as Tantalos and Co. had done. The next tale -- that of Tereus, Procne and Philomela -- concerns mortals alone. Yet as we'll see, the making of image, of self-image, and of voice return in that tale, horrifically.

My point is simply to remember that the tales of Book 6, mostly set in Asia Minor, take place in the land of one of the most enigmatic ancient characters, the son of Zeus and Pluto. Pindar's 1st Olympian continues:

that man was Tantalus.

But he was not able to digest his bliss,

and for his greed he gained overpowering ruin,

which the Father hung over him: a mighty stone.

Always longing to cast it away from his head,

he wanders far from the joy of festivity.

He has this helpless life of never-ending labor,

a fourth toil after three others,

because he stole from the gods nectar and ambrosia,

with which they had made him immortal,

and gave them to his drinking companions.

If any man expects that what he does escapes the notice of a god,

he is wrong.