(Edited to clarify and added the Rubens)

At the end of Metamorphoses 12, Achilles falls to the arrow of Paris, guided and prompted by Apollo, who was stirred to action by Poseidon.

Ovid writes:

Of course the word "fame" is actually gloria:

In addition to the distinction between the mortal remains of Achilles - barely enough to fill an urn - and his glory, which lives to fill the entire world (orbem, the realm of Fama), we note a favorite construction of classical authors, the chiasmus:

The chiastic structure of the line: A - B : B - A plays out the mystery of the relation of human and divine in a demigod like Achilles -- he is both protected from injury and incinerated by the same god, in this case Hephaestus, or Vulcan. The sounds replicate the sense -- idem means "the same," and the same word is twice used. Armarat . . . cremarat reflect each other in syntax, meter, and sound.

The concentric shape of the line is not unlike the shape of the west pediment of the Parthenon, which tells the contest of Athena and Poseidon for the city of Athens, which forms a major feature of Metamorphoses 6 (click to enlarge the image:)

The pediment's balanced, formal symmetry places the chief figures in the center, with each half reflecting the other in geometric structure and sense.

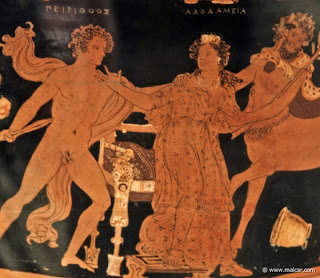

It never hurts to look for chiastic structure, also known as ring structure, in classical works. The savage wedding of book 12 appears to reflect the brutal wedding feast of Perseus in Books 4 and 5. Achilles' glory fills the orbem at the end of book 12, reminding us of the world (orbem) of Fama at the book's beginning.

We might look at the death of Achilles in some detail, and ask: in this book that pays its strange Ovidian homage to Homer, to the epic, and to the Trojan War, why is there so little focus on the actual work of war between human actors who fight and one dies at the hands of the other?

At the end of Metamorphoses 12, Achilles falls to the arrow of Paris, guided and prompted by Apollo, who was stirred to action by Poseidon.

Ovid writes:

Now Achilles, grandson of Aeacus, the terror of the Phrygians, the glory and defence of the Pelasgian name, the invincible captain in battle, was burned: one god, Vulcan, armed him, and that same god consumed him. Now he is ash, and little if anything remains of Achilles, once so mighty, hardly enough to fill an urn. But his fame lives, enough to fill a world. That equals the measure of the man, and, in that, the son of Peleus is truly himself, and does not know the void of Tartarus. (Kline).

Of course the word "fame" is actually gloria:

Iam timor ille Phrygum, decus et tutela Pelasgi

nominis, Aeacides, caput insuperabile bello,

arserat: armarat deus idem idemque cremarat;

iam cinis est, et de tam magno restat Achille 615

nescio quid parvum, quod non bene conpleat urnam,

at vivit totum quae gloria conpleat orbem.

haec illi mensura viro respondet, et hac est

par sibi Pelides nec inania Tartara sentit.

In addition to the distinction between the mortal remains of Achilles - barely enough to fill an urn - and his glory, which lives to fill the entire world (orbem, the realm of Fama), we note a favorite construction of classical authors, the chiasmus:

armarat deus idem idemque cremarat;

armed by a god, the same god consumed him.

|

| Rubens: Vulcan Presents Arms of Achilles to Thetis |

The chiastic structure of the line: A - B : B - A plays out the mystery of the relation of human and divine in a demigod like Achilles -- he is both protected from injury and incinerated by the same god, in this case Hephaestus, or Vulcan. The sounds replicate the sense -- idem means "the same," and the same word is twice used. Armarat . . . cremarat reflect each other in syntax, meter, and sound.

The concentric shape of the line is not unlike the shape of the west pediment of the Parthenon, which tells the contest of Athena and Poseidon for the city of Athens, which forms a major feature of Metamorphoses 6 (click to enlarge the image:)

The pediment's balanced, formal symmetry places the chief figures in the center, with each half reflecting the other in geometric structure and sense.

It never hurts to look for chiastic structure, also known as ring structure, in classical works. The savage wedding of book 12 appears to reflect the brutal wedding feast of Perseus in Books 4 and 5. Achilles' glory fills the orbem at the end of book 12, reminding us of the world (orbem) of Fama at the book's beginning.

We might look at the death of Achilles in some detail, and ask: in this book that pays its strange Ovidian homage to Homer, to the epic, and to the Trojan War, why is there so little focus on the actual work of war between human actors who fight and one dies at the hands of the other?