In Book 9, as Prof. Anderson notes, Ovid introduces the act of writing into the scene of Byblis in love with her twin brother. It is an opportunity for Ovid once again to capitalize on a mirroring effect -- just as the girl loves an image of herself, so the depiction in writing of a writer writing offers a reflection upon its own production.

As the girl moves from discovery to confession to excuse to a vow to "conquer" her brother's love, she dramatizes the full gamut of rhetorical arts and strategies. It's a portrait, or meta-portrait, of the author as one who both seeks to find a way to name (nomine) the secrets of the heart and to conquer (vincere) the reader.

Writing is naming, re-writing and seduction, Ovid seems to say. Writers may seem to be impassioned Rousseaus nakedly revealing the insupportable wounds of the heart, but what author is not at the same time concerned to succeed with his/her public? Writing can both say and do, and these do not necessarily always coincide. The intricate interplay of passion, desire, deletion, search for the mot juste, plot, strategy, pathos and calculation is fully exhibited in the scene where Byblis writes on her wax tablet:

in latus erigitur cubitoque innixa sinistro'viderit: insanos' inquit 'fateamur amores!ei mihi, quo labor? quem mens mea concipit ignem?' et meditata manu componit verba trementi.dextra tenet ferrum, vacuam tenet altera ceram.incipit et dubitat, scribit damnatque tabellas,et notat et delet, mutat culpatque probatqueinque vicem sumptas ponit positasque resumit. quid velit ignorat; quicquid factura videtur,displicet. in vultu est audacia mixta pudori.scripta 'soror' fuerat; visum est delere sororemverbaque correctis incidere talia ceris:'quam, nisi tu dederis, non est habitura salutem, hanc tibi mittit amans: pudet, a, pudet edere nomen,et si quid cupiam quaeris, sine nomine vellemposset agi mea causa meo, nec cognita Byblisante forem, quam spes votorum certa fuisset.

So raysing up herself uppon her leftsyde shee enclynd, And leaning on her elbow sayd: Let him advyse him whatTo doo, for I my franticke love will utter playne and flat. Alas to what ungraciousnesse intend I for to fall?What furie raging in my hart my senses dooth appall?

In thinking so, with trembling hand shee framed her to wryght The matter that her troubled mynd in musing did indyght. Her ryght hand holdes the pen, her left dooth hold the empty wax. She ginnes. Shee doutes, shee wryghtes: shee in the tables findeth lacks. She notes, she blurres, dislikes, and likes: and chaungeth this for that.

Shee layes away the booke, and takes it up. Shee wotes not what She would herself. What ever thing shee myndeth for to doo Misliketh her. A shamefastnesse with boldenesse mixt theretoWas in her countnance. Shee had once writ Suster: Out agen The name of Suster for to raze shee thought it best. And then

She snatcht the tables up, and did theis following woords ingrave: The health which if thou give her not shee is not like to have Thy lover wisheth unto thee. I dare not ah for shame I dare not tell thee who I am, nor let thee heare my name. And if thou doo demaund of mee what thing I doo desyre,

Would God that namelesse I myght pleade the matter I requyre, And that I were unknowen to thee by name of Byblis, till Assurance of my sute were wrought according to my will.

Metamorphoses Book 9, Golding translation

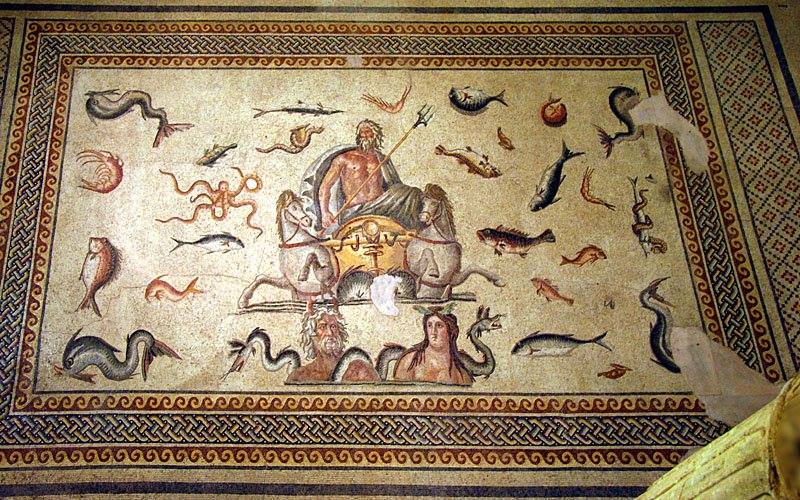

The image of the wax tablet comes from an interesting page on the history of writing.