The other day, as we were reading aloud the story of

Scylla, the daughter of Nisus, and the siege of

Megara, a few strange features of the tale stood out.

The horns of a new moon had risen six times and the fortunes of war still hung in the balance, so protractedly did Victory hover between the two, on hesitant wings. There was a tower of the king, added to walls of singing stone, where Apollo, Latona’s son, once rested his golden lyre, and the sound resonated in the rock. In days of peace, Scylla, the daughter of King Nisus, often used to climb up there, and make the stones ring using small pebbles. In wartime also she would often watch the unyielding armed conflicts from there, and now, as the war dragged on, she had come to know the names of the hostile princes, their weapons, horses, armour and Cretan quivers. Above all she came to know the face of their leader, Europa’s son, more than was fitting. (Kline)

We were reminded of Helen and Priam, looking out upon the opposing armies before Troy. Unlike Helen, Scylla is not the cause of the war, but she does have knowledge of the vulnerable purple hair of her father, King Nisus. Knowledge, in her case, is power -- she has the means of ending this uncertain siege.

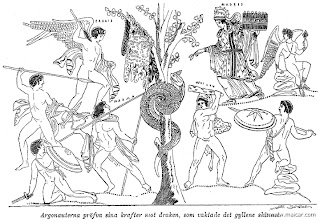

|

| Minos and Scylla |

Sieges often depend upon walls, and the walls of Megara were special. They were built for

Alcathous, son of Pelops, by Apollo. Alcathous had built temples to both Apollo and Artemis after killing the Cithaeronian Lion and winning the hand of the princess of Megara. During construction, Apollo lay down his golden lyre, making the walls where it rested resonant --

saxo sonus eius inhaesit. Scylla had been drawn to this place before the war, tossing little stones to hear it ring. It's here that she now falls in love with King Minos, who's trying to sack Megara as part of his war on Athens precipitated by the death of his son, Androgeos. (Other cities had charmed walls -- the Cadmea was raised by the music of

Amphion).

Two odd features of this tale:

1. Instant closeness to the distant other, distance from one's own: From her perch on the parapet of Megara, Scylla seems like any adolescent watching TV. The consequential reality of the war doesn't enter her mind. She's completely conquered by Minos, whom she's only seen from afar, and around whom she's constructed a story. Minos has no idea of her existence until she appears at his camp with her father's purple lock. Like Medea, she betrays her father, city, and people, but unlike Jason's helper, she has no opportunity to make his pledge of commitment a precondition of her fateful act. Her decisive act precipitates out of a flight of fantasy.

O ego ter felix, si pennis lapsa per auras

Gnosiaci possem castris insistere regis

O I would be three times happy if I could take wing, through the air,

and stand in the camp of the Cretan king

When Minos shrinks from her in revulsion, she feels betrayed.

It's clear that Scylla has been so charmed as to lose all grounding in her historical, ethical and material reality. Her fascination with Minos (who, astride his white horse, wearing royal purple, from a distance might resemble her father's regal head) draws her from realities into a Quixotic dream.

She fancies that she is equal to the great deeds of other heroines:

Another girl, fired with as great a passion as mine, would, long ago, have destroyed anything that stood in the way of her love.

|

| Ciris |

Horrified by her action, the king of Crete calls Scylla an infamy, a monster (

infamia, monstrum). He's about to discover further infamy, closer to home, and "another girl," his own daughter, who will open the heart of the labyrinth to Theseus.

Both stories -- Scylla and Nisus, Minos and Ariadne -- link victory not to martial prowess, but to the destructive power of wounding

amor that finds the vulnerabilities of mighty walls and daedal defenses. (Ovid never tires of

turning pitched battles into love tales.)

The narrator doesn't share insight into the motives of

Amor, but:

2. An end uncannily near its beginning: More speculatively, the extreme infatuation of Scylla seems bound up with the lyrical place where it takes hold. It's as if this girl, moved by the echoes of Apollo's lyre, could not but fall for this shining king. The question, then, might be: As the god of prophecy, Apollo must have known that setting down his lyre on the walls would end in the fall of the city. In helping Alcathous to restore the defenses (which had been once before

brought down by Crete), did Apollo "happen" to build into their fabric a fatal charm? One that leads to another sacking by Cretan force? An echo?

15

There was a tower of the king, added to walls of singing stone,

and the sound resonated in the rock

The walls of Megara, it seems, have been vibrating with fatal song since they were rebuilt. That they are

vocalibus -- speaking, sonorous, singing, crying -- suggests that inherent in their fabrication,

clinging to it, was the song of their destruction, the "thing spoken":

fate  late 14c., from L. fata, neut. pl. of fatum "prophetic declaration, oracle, prediction," thus "that which is ordained, destiny, fate," lit. "thing spoken (by the gods)," from neut. pp. of fari "to speak," from PIE *bha- "speak" (see fame). The Latin sense evolution is from "sentence of the Gods" (Gk. theosphaton) to "lot, portion" (Gk. moira, personified as a goddess in Homer), also "one of the three goddesses (Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos) who determined the course of a human life." Related: Fated; fating. The native word was wyrd.

late 14c., from L. fata, neut. pl. of fatum "prophetic declaration, oracle, prediction," thus "that which is ordained, destiny, fate," lit. "thing spoken (by the gods)," from neut. pp. of fari "to speak," from PIE *bha- "speak" (see fame). The Latin sense evolution is from "sentence of the Gods" (Gk. theosphaton) to "lot, portion" (Gk. moira, personified as a goddess in Homer), also "one of the three goddesses (Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos) who determined the course of a human life." Related: Fated; fating. The native word was wyrd.

What will be sung was woven in the warp of the world when it began. For Ovid, it's the song he's singing to us. (For us, it's the song we hear through the meta -ana- morphosis of interpretation.) It was put there by the god of poetry and prophecy, who so happened to set his fatal lyre down, the way Perseus set down the head of Medusa, and created

coral.

|

| Sea Eagle, or Haliaeetus |

Beginning and end are very close here -- like your DNA and you -- almost "the same," yet not entirely, and not harmoniously. As Minos sails to his destiny, the Sea-Eagle swoops down to tear the treacherous child who betrayed the sleeping king. She clings (

haeret) to the bark of Minos, then drops in terror into endless flight.