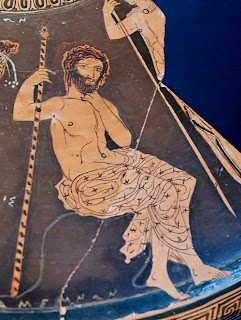

The ivory prosthesis Pelops reveals as he mourns for his sister sets him apart from all men as the son of Tantalos, returned after horrible dismemberment. Here's the brief passage in Book 6 in which Pelops mourns for Niobe, his sister:

even then one man, her brother Pelops, is said to have wept for her and, after taking off his tunic, to have shown the ivory, of his left shoulder (umero). This was of flesh, and the same colour as his right shoulder, at the time of his birth. Later, when he had been cut in pieces, by his father, it is said that the gods fitted his limbs together again. They found the pieces, but one was lost, between the upper arm and the neck. Ivory was used in place of the missing part, and by means of that Pelops was made whole (integer).

The positioning of this Pelops vignette is worth thinking about. It immediately precedes Ovid's tale of Philomela that ends with a father, Tereus, dining on his own son, who has been killed, dismembered and prepared for a "sacred feast" by Procne, the child's mother and Tereus' wife.

The glimpse of Pelops' ivory shoulder "fits" the themes of Book 6 in so far as his restoration is a collective work of art of the gods, bringing back the beloved boy, as Ovid says,

integer -- thanks to the prosthetic addition, necessary thanks to Demeter's distraction.

This integrity of the reconstituted Pelops (presented more as a work of restoration than a resurrection) stands in clear contrast to the disintegration that immediately follows -- the

Grand-Guignol tale of the Thracian king who violates the trusts of office and family, mutilating and imprisoning Philomela in order to suppress her power to tell the world of his vile rape.

Yet she doesn't remain silent, despite the loss of her tongue. Thanks to

ingenium and

sollertia -- her inwit and cunning -- the girl creates an artificial thing, an image, that fills the void of her tongue. Supplementary and not dependent on presence, the image is external to her; it can be transported without being seen, yet speaks ventriloquially to the one it is intended for. It's a metamorphic prosthesis of her voice that makes her "whole."

Look at what happens when the image of Philomela's voice reaches the eyes of her sister:

miserabile legitet (mirum potuisse) silet. Dolor ora repressitverbaque quaerenti satis indignantia linguaedefuerunt; nec flere vacat, sed fasque nefasqueconfusura ruit, poenaeque in imagine tota est.

The wife of the savage king unrolls the cloth, and reads her sister’s terrible fate, and by a miracle keeps silent. Grief restrains her lips, her tongue seeking to form words adequate to her indignation, fails. She has no time for tears, but rushes off, in a confusion of right and wrong, her mind filled with thoughts of vengeance.

The "voice" of Philomela is so potent it takes away Procne's power of speech -- it partakes of the unspeakable. Kline's translation says Procne's mind is filled with "thoughts of vengeance," but Ovid chooses to continue the sense of the visual, and says

poenaeque in imagine tota -- Procne's mind is consumed and confused by the deranging power of this

image, much as is Tereus's mind the first time he beheld Philomela:

Quid quod idem Philomela cupit patriosque lacertis VI.475 blanda tenens umeros, ut eat visura sororem, perque suam contraque suam petit ipsa salutem. Spectat eam Tereus praecontrectatque videndo osculaque et collo circumdata bracchia cernens omnia pro stimulis facibusque ciboque furoris accipit;

Moreover Philomela wishes his request granted, and resting her forearms on her father’s shoulders, coaxing him to let her go to visit her sister, she urges it, in her own interest, and against it. Tereus gazes at her, and imagining her as already his, watching her kisses, and her arms encircling her father’s neck, it all spurs him on, food and fuel to his frenzy. (Kline)

With a poet as careful as Ovid, could it be by chance that "shoulders," "neck," and "food" are interwoven here? Inscribed in Tereus' vision of the girl pleading with her dad are key words linked to the sacrilege of Tantalos, the horrific violation of divine proprieties, the curse Tereus is to reenact with his son, Itys. Both Tereus and Procne are driven to frenzy by what they see.

Amor -- the fire that sets Tereus ablaze for Philomela -- simultaneously images his doom.

In this, the only tale of Book 6 in which the key players are human, there's no saving grace, no restoration. As each character in turn undergoes a loss of balance, of moral center, in which every human bond vanishes, the void is filled with theatricality (Tereus's pleas, Procne's bacchantes, the feast).

Why does Ovid place this tale of human degeneration next to story of divine regeneration? No divinity is pulling the strings, no Juno or Hermes is causing Tereus, Procne and Philomela to do what they do.

In this tale, humans cannot cast blame upon some supernatural being for their actions, any more than

Lykaon could for his heinous crime of inviting Jupiter to dine on a human in Book I. This time, no one can say, "the devil made me do it."