|

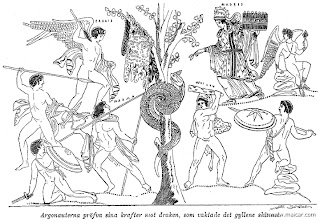

| Crewman of Odysseus turning into a beast |

A new tale of Circe, told from the point of view of the daughter of Helios, is just out. It's by Madeline Miller, author of The Song of Achilles.

The scope of the tale as told by Miller reckons with the reality of status as an immortal. Odysseus's visit to her isle, while memorable, is but a blip:

"In Ms. Miller’s version, Circe’s encounter with Odysseus is only a slice of her story, which unfolds over thousands of years and begins in the palace of her father, the sun god Helios. Her family members, who treat her with cruelty or indifference, become infamous in their own right: Her sister Pasiphae marries King Minos and gives birth to the Minotaur, a bullheaded, man-eating monster; while her brother Aeetes grows up to rule Colchis, the land of the Golden Fleece, and fathers Medea, who later murders her children." NYTMyths as the ancients told them were galaxies filled with tales, stretching through generations, with cities and kings rising and falling. Miller seems alive to that scale of things. Her blog, enriched by her Greek and Latin, is titled "Myths."

And, as noted in reading the Metamorphoses, Ovid's wit is urbane and literary. In his telling, the myths are changed, at points with parodic effect. Understandably, Miller doesn't draw upon his version of the enchantress.

deliberately omitting a scene from Ovid’s Metamorphoses where Circe punishes a king who spurns her advances by turning him into a woodpecker.

|

| Madeline Miller |