Ovid seems never to miss an opportunity to interweave some odd factoid, or bit of legend, into his narrative, introducing these elements seemingly at random. We recall in Book 4, after Perseus had put the head of Medusa on the ground, we are offered a fine description of how it turned living plants into coral, living rock.

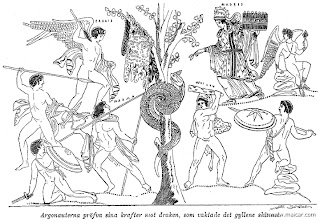

In Metamorphoses 7, Ovid takes pains to describe organic modes of development at moments that don't seem to call for them. Here's Jason sowing the dragon's teeth, repeating Cadmus's famous act in Book 3, prior to the founding of Thebes. While Cadmus's warriors rose immediately from his toothy seeds, Ovid gives Jason's a more gradual, organic development:

Then he took the dragon’s teeth from the bronze helmet, and scattered them over the turned earth. The soil softened the seeds that had been steeped in virulent poison, and they sprouted, and the teeth, freshly sown, produced new bodies. As an embryo takes on human form in the mother’s womb, and is fully developed there in every aspect, not emerging to the living air until it is complete, so when those shapes of men had been made in the bowels of the pregnant earth, they surged from the teeming soil, and, what is even more wonderful, clashed weapons, created with them. 7.123 ffLater, as Medea arrives in Corinth, we learn in passing that the people of that city derived from rain-soaked mushrooms:

At last, the dragon’s wings brought her to Corinth, the ancient Ephyre, and its Pirenian spring. Here, tradition says, that in earliest times, human bodies sprang from fungi, swollen by rain. 7.391 ffAnd when Medea is preparing to poison Theseus to secure the Athenian succession for her own son, we learn the origin of wolf-bane, from the slobber of the hound of hell:

Medea, seeking his destruction, prepared a mixture of poisonous aconite, she had brought with her from the coast of Scythia. This poison is said to have dripped from the teeth of Cerberus, the Echidnean dog. There is a dark cavern with a gaping mouth, and a path into the depths, up which Hercules, hero of Tiryns, dragged the dog, tied with steel chains, resisting and twisting its eyes away from the daylight and the shining rays. Cerberus, provoked to a rabid frenzy, filled all the air with his simultaneous three-headed howling, and spattered the green fields with white flecks of foam. These are supposed to have congealed and found food to multiply, gaining harmful strength from the rich soil. Because they are long-lived, springing from the hard rock, the country people call these shoots, of wolf-bane, ‘soil-less’ aconites. 7.405 ffThese brief, gratuitous-seeming bits of lore and detail support the very Ovidian notion that underlying all appearances is change, and you neither know what something might turn into, nor can necessarily be sure what it came from. It certainly might come as news to some Corinthians that their ancestors were wet mushrooms. (Mycenae is also said to derive from "μύκης" (mycēs) = mushroom.)

We might press further, and suggest that these three miniature tales of generation all share asexuality. Mushrooms grow from spores, which are more like bacteria than like seeds, and depend on the richness of surrounding soil to grow. They also do not need light. We might speculate that the same holds true for dragon's teeth and Cerberus' saliva (the description of which sounds awfully bacteriological) -- neither stores food nor needs the sun. Yet things emerge from them.

Are there further nuances? Are we, for example, to think to compare Jason's feat with that of Cadmus? Cadmus's tale is largely a denial of the womb -- after he fails to find his sister Europa, his city springs from males who instantly rise up, without the benefit of slow development (and his tale ends with Pentheus being killed by his mother). Jason's quest for the fleece succeeds in large part due to the mediation of Medea. It's worth noting that Cadmus founded a doomed city, while Jason, after returning with the fleece, went on to found nothing, and to lose his children to the very woman who "made" him what he was. Jason even receives his best-known epitaph from Euripides' witch:

you, a coward, you will die a coward's death as you deserve,Is there a further contrast between the slow generation of the warriors sown by Jason, and the inorganic use of natural materials drawn from all over the world, in Medea's magic, to do the most unnatural thing of all, to make the aged Aeson again young?

struck on your head by a remnant of the wreck of the Argo

seeing a bitter end to your marriage to me.

These might seem idle thoughts, but the second half of book 7, which approaches the center of the poem, concerns the marvelous generation of an entire people, thanks to the holy Aeacus (or Aeakos), son of Zeus and Aegina, and grandfather of Achilles. As we have observed, Ovid links his tales in strange ways.

Share

Share